Charleston Harbor looks calm from above. The surface reflects church spires, shrimp boats, and soft evening light. Below that calm water, shipwrecks rest in sand and silt. These wrecks hold a record of trade, war, and storms.

Charleston’s story stays tied to the sea. The harbor connected the city to the Atlantic for centuries. Ships arrived with cargo, crews, and news from far ports. Some ships never left again. A tide changed. A channel shifted. A storm hit. A battle closed in.

Why Charleston Harbor Has So Many Shipwrecks

Charleston grew as a working port, and heavy traffic brought risk. Shallow bars and shifting bottom conditions could trap a hull at the wrong moment. Storm weather could turn an anchored ship into wreckage in minutes.

War added another layer. During the Civil War, Charleston Harbor became a long naval battlefield. Researchers at the University of South Carolina mapped the “Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield” and documented wrecks, obstructions, and related sites from both sides of the conflict.[1]

Colonial-Era Losses and Early Trade

In the 1600s and 1700s, Charleston rose as a major port for goods like rice and indigo. Merchant ships ran close to shore, and coastal storms could catch them fast. Some wrecks appear in written records. Other wrecks remain unnamed under the harbor floor.

These earlier sites matter because they can show how trade worked and how shipbuilders solved problems with the materials they had.

Civil War Shipwrecks You Can Still Point To on a Map

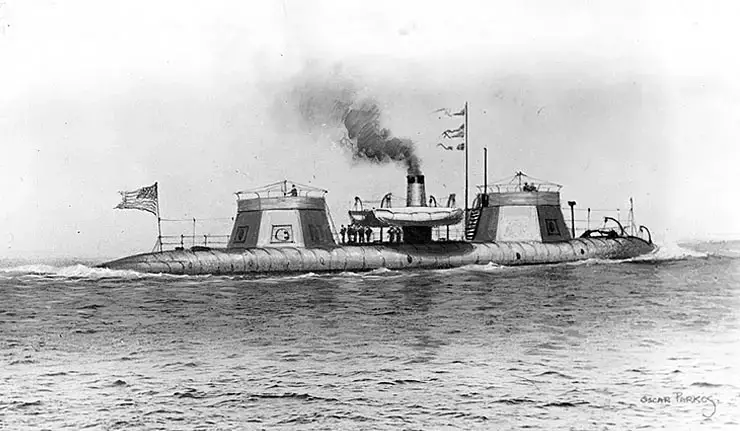

The Civil War left some of the best-known shipwreck history in and near Charleston Harbor. Several ironclads and other vessels went down in this area, and some remain underwater today. The South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology notes three ironclads that rest on the harbor floor: USS Patapsco, USS Keokuk, and USS Weehawken.[1]

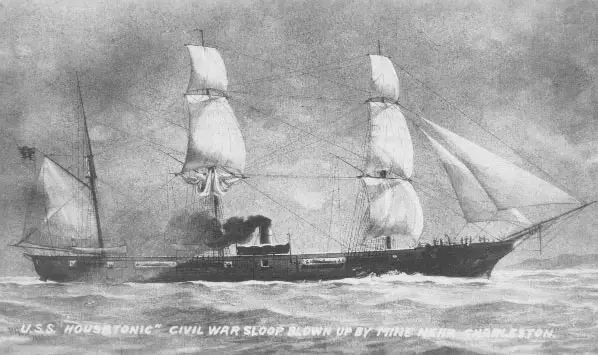

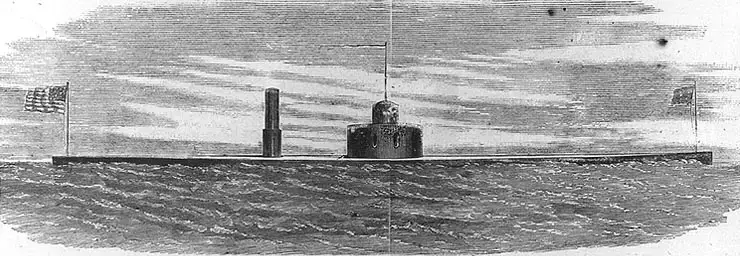

H.L. Hunley and USS Housatonic

On February 17, 1864, the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley attacked USS Housatonic on blockade duty just outside the harbor entrance. The Navy’s history office describes Hunley’s spar torpedo attack and notes that Housatonic sank after the strike.[2]

Hunley matters because it marked a turning point in naval warfare. It is widely recognized as the first submarine to sink an enemy warship in wartime.[3]

USS Keokuk

USS Keokuk was an experimental ironclad that took heavy damage during the Union attack on Charleston’s defenses in April 1863 and sank soon after.

Keokuk left a visible “after-story” on land. One of its large 11-inch Dahlgren guns was salvaged after the sinking and later placed at White Point Garden. The Charleston Museum’s collection notes the gun’s Keokuk connection and placement in the park in 1899.[5]

USS Weehawken

USS Weehawken, a Union monitor, sank at anchor off Charleston in a gale on December 6, 1863. The wreck remains part of the harbor’s Civil War record.

USS Patapsco

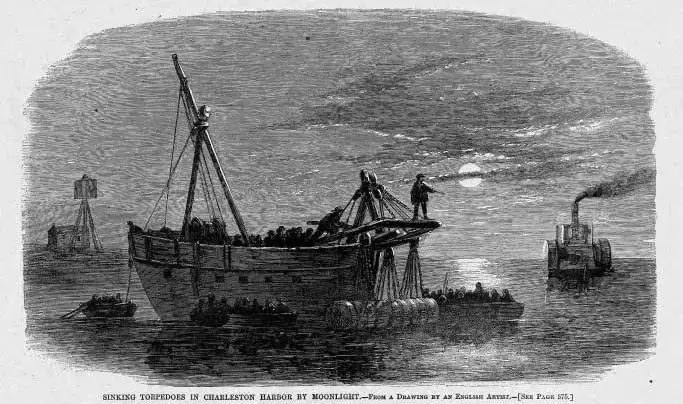

USS Patapsco, another Union monitor, sank after it struck a Confederate mine (often called a “torpedo” at the time) while operating in Charleston Harbor. The wreck remains a wartime memorial site.

A Man-Made Ship Graveyard: The Stone Fleet

Not every ship went down by accident. In late 1861, the Union sank a group of old whaleships loaded with stone to obstruct Charleston’s channels. The Smithsonian description of the Stone Fleet states that 24 whaleships were sunk in Charleston Harbor on December 19, 1861 as part of the blockade effort.[4]

Even without seeing a wreck, visitors can picture what that meant: a harbor entrance turned into a barrier, built from ships that were already near the end of their working lives.

What People Have Actually Found

Some of the most direct “harbor finds” come from the Hunley recovery and excavation work.

Conservators recovered a warped 1860 twenty-dollar gold coin associated with Hunley commander George E. Dixon. Clemson University describes the coin as being recovered from Dixon’s remains and displayed at the conservation center.[6]

The Friends of the Hunley describe jewelry discovered during sediment excavation in 2002, including a diamond ring and a diamond brooch found at Dixon’s station area inside the submarine.[7]

These are small items, but they change the story. They make the past feel close, because they came from pockets and hands, not just logs and maps.

Where Are These Wrecks Located? (General, Safe Locations)

- USS Housatonic: Offshore near the entrance to Charleston Harbor, outside the main shipping channels.

- USS Keokuk: Near the approaches to the harbor, off Morris Island.

- USS Weehawken: Off Morris Island, where the ship sank at anchor during a gale.

- USS Patapsco: Inside Charleston Harbor, where the ship struck a mine while operating in the area.

- Stone Fleet: In harbor channel areas near the entrance that ships used to enter and leave the port.

If you want to explore these stories, use museums, archives, and licensed tours. Do not disturb wrecks. Do not remove artifacts.

From Wreck to Habitat

Time changes shipwrecks. Timber softens. Iron corrodes. Marine life settles in. Many wrecks become structure that fish and shellfish use for cover.

Archaeologists also study wreck sites for evidence of trade, ship construction, and daily life at sea. Many underwater cultural sites are protected by law, and people should not remove artifacts or disturb wrecks.

Experience the Harbor Above the Wrecks

Most shipwrecks stay out of sight. Their stories still rise through museum exhibits, local history work, and guided tours. A boat trip adds something a book cannot. It places you on the same water where these events happened.

Carolina Marine Group offers private charters in Charleston Harbor. Your route can pass through areas tied to shipping lanes, wartime defenses, and storm history. You may not see a wreck on the surface, but you can feel how the harbor holds its past just below the waterline.

If you want a private Charleston Harbor boat charter, contact Carolina Marine Group to plan a trip.

FAQ: Shipwrecks in Charleston Harbor

What are the most famous shipwrecks tied to Charleston Harbor?

Notable Civil War wrecks in the area include H.L. Hunley (linked to the sinking of USS Housatonic), USS Keokuk, USS Weehawken, and USS Patapsco.

Was the Stone Fleet really sunk in Charleston Harbor?

Yes. The Smithsonian describes a fleet of 24 whaleships sunk in Charleston Harbor on December 19, 1861 as part of the blockade strategy.[4]

Can I dive to see shipwrecks in Charleston Harbor?

Rules vary by site and many locations have legal protections. Always follow local, state, and federal regulations.